Currently nearing its end, the exhibition “These are the days I (have) love(d),” in which the New York City art gallery Bortolami spotlights artist Christine Safa, is a standout.

The work was put on view at an upstairs gallery space at 39 Walker Street, and although the nearby area is bustling with other art exhibitions on a regular basis, this is a quieter spot that’s removed from the main bulk of passersby. It’s only accessible via entering Bortolami’s adjoining, ground-level gallery space, and the paintings — hanging quietly on the walls in a room that I’ve also seen overtaken by very large pieces — keyed into a more restrained side to the space, which set Safa’s works up nicely.

Safa’s Dreamily Shifting Environments

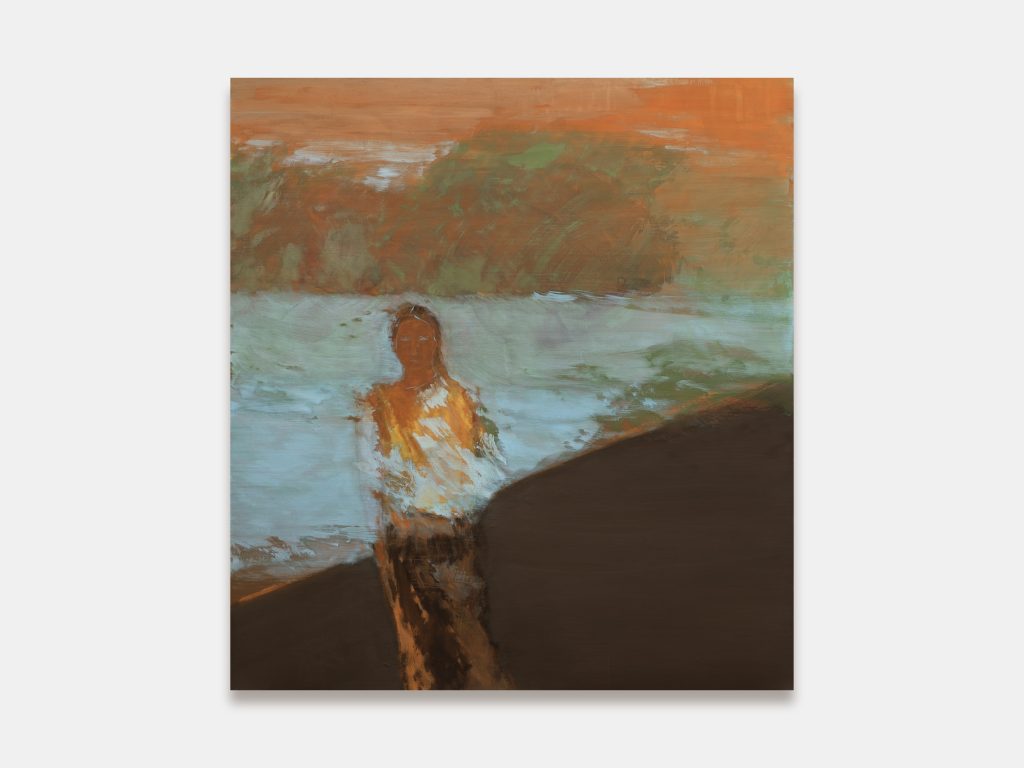

Safa places human figures amid surrounding environments like a house — seen in possibility-rich, apparent isolation — and, in another, a waterfront, but none are presented with pristine clarity. Safa instead crosses the conceptual bounds of representing the physical, with cues that direction alongside dreamy, uplifting bursts of color that decidedly exit the physical.

The figures’ faces don’t have much detail, and they’re overlaid on their surroundings rather than crisply distinguished, with any sense of depth gone or on its way out. In materials made available by the gallery, Safa speaks about hearkening to her memories with the construction of these works, and visually, that’s strikingly evident.

Safa’s paintings suggest that memories of a person and a place tend to exist within the same theoretical space in the mind, blending into each other until the place bursts with personality and the person, loved and perhaps lost (at least for the moment), becomes a sweeping presence ensnaring you. That’s the appearance given to both those sides of the real-world experiences towards which Safa moves: growth beyond their nature and a person or place you remember more as a billowing set of feelings than a series of scientific measurements.

When accompanied by an environment, Safa’s figures are specters of varying transparency that lay atop rich, consuming backgrounds: people who look like you’re seeing them only peripherally or trying to reconstruct a memory from encounters either just brief or fading further into the past, like a loved one you haven’t seen in a long while. The rhythmic ease of Safa’s paintings hearkens to natural, expected processes like the slowly degrading effects of time, bringing to the mental forefront a version of even your own self that is left to the rhetorical shifting sands of what came before and won’t again.

Merging into a New Presence

In this series of paintings, everything is, time and again, on the same plane, as though merging both physically and emotionally into something new: a delicate but growing, intangible materialization of recollecting an experience that balances between its point in your history and your present, like a mediator. The memory becomes its own person, conceptually separate from its contents or original starting point.

The visual style reminds me of impressionism, although the image-altering factors that Safa is capturing seem internal rather than environmental.

Safa caught the pieces of these slipping experiences before they completely dissolved from distinguishable view, but the sweeps of color in the more “abstract” areas are so encompassing that the processes of dissolution and intermingling look fully underway: a perspective of time passing and how we can’t do, well, anything about it. The pace at which fog-like recollections of a person or a place merge into each other is, though, peaceful rather than aggressively upending. The flow of Safa’s sweeps of color seems reassuring, in the end.

Even though Safa’s images touch outside the representational, each still seems to visually encapsulate a perceptible experience, with the deconstructing strain of time’s passing given weight equal to a more spiritually enlivening perspective on entropy: pulling apart but pushing together.

Safa’s “Silence, en été” (2024), a standout, is a close-up view of a face, identified as such by mere outline, a suggestion of light, and a crowning area of hair — with the actual contents of the face left almost completely absent, though there are slight textures in the application of paint.

And in “Le jardin (Lozère)” (2024), there’s no clear way to tell who the person in the image might be without knowing the artist’s personal context, but you still feel like you’re looking at someone’s imprint. In “Le Sporting” (2023), from a distance you might clock a certain shape on the canvas as a setting sun against a horizon before moving closer to find it’s the head of a faintly visible figure, visually merging with its churning background that looks startlingly alive for a landscape as clouds of orange and purple intermingle.

The gaps that Safa leaves in her images between what we can ascertain that she’s referencing from her real-world experiences and how these paintings actually look ultimately leave space for longing — looking for the clearer iterations of an image but accepting if it doesn’t come. The exhibition is perhaps surprisingly but persistently calm, approximating the progression of a setting sun.

Safa’s exhibition “These are the days I (have) love(d)” continues at Bortolami through June 8, after which I’m looking forward to what comes next from the artist.

Featured image: Same as above

You may also like

-

Diana Kurz at Lincoln Glenn in New York: A Review of a Shining Art Exhibition

-

Dustin Hodges at 15 Orient in New York City: An Ensnaring Exhibition at an Exciting Gallery

-

Maren Hassinger at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York: Reviewing an Uplifting Art Exhibition

-

Enzo Shalom at Bortolami in New York City: Reviewing an Entrancing Exhibition of Paintings

-

“Ben Werther: Townworld” at Amanita in New York City: Reviewing a Richly Memorable Art Exhibition