Among the most memorable artworks for me at this year’s Whitney Biennial were suspended paintings from longtime artist Suzanne Jackson.

The biennial is a recurring exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, offering a survey of the latest and greatest in art. This year, much of the artwork focused on the many diverging — and sometimes converging — ways that artists and the communities they represent might try and negotiate a sense of “reality,” whether on a personal or collective level.

The Work of Suzanne Jackson

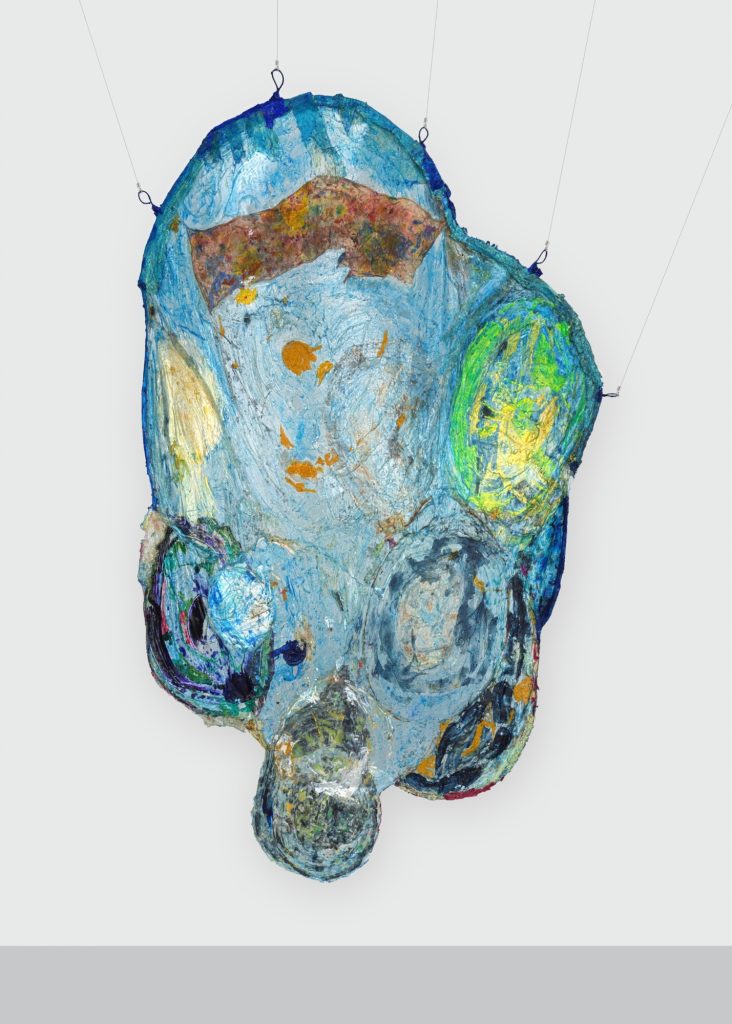

Jackson’s “paintings” featured no canvas backing — or rigid backs of any sort. Instead, the binding agent for Jackson’s panoplies of pigment and materials was an acrylic gel medium — a clear, gel substance to which Jackson added acrylic paint and items like netting and vintage dress hangers.

Jackson’s particular process made this series of artworks both “paintings” and sculptural works lifting well beyond the context and manner in which paints are often used elsewhere — centering the textural qualities of paint and materials Jackson chose to accompany it.

So, you can think about these works in terms of both image creation and crafting an art object, the latter fueled by the physical relationships in three-dimensional space of Jackson’s artistic ingredients and what they evoke.

In general, the visual rhythms across each piece struck me as remarkably cohesive — and even homely, the latter leaning in part on the familiarity of some items that Jackson added beyond the acrylic varieties.

“Red over morning sea” (2021) included shredded mail within the gel — plus curtain lace, produce bag netting, and more. “Singin’, in Sweetcake’s Storm” (2017) featured pistachio shells. A rectangle hung from one of its ends, that particular artwork also evoked a bed. Another, “Rag-to-Wobble” (2020), looked slightly figure-like in its overall shape, with a rounded protrusion at the bottom that resembled a head on a pair of shoulders.

Bringing the Artistic Parts Together

But there was more than straightforward familiarity. In categories like color relationships, Jackson’s pieces flowed smoothly. It’s striking, really. Though there was really a lot going on in logistical terms, nothing looked chaotic or messy, as much as those qualities can be artfully invoked elsewhere. They’re not inherently “bad” choices in art; they’re just not how these works came across.

And in terms of three-dimensional space, Jackson’s artistic components moved just as much upwards and away as back towards viewers, comprising a self-replenishing artistic ecosystem. As much as the gel makes you surprised the artworks would stay together at all, there’s a unifying consistency, even when what Jackson added starts to make the gel imperceptible.

They’re not visually overwhelming at all; instead, they’re welcoming.

The back-and-forth movement between parts of each individual artwork evoked the non-verbal language of a place — and a path through life — molded according to some individual’s preferences and opportunities.

It’s an elevation of the moments in between the “bigger” moments, unified into their own “big” thing and given the spotlight. The swing of an hour into the next — checking the mail, throwing out the trash, feeding the birds, and then doing it all again tomorrow. And on a bigger scale, you get a sense of forging personal presence from sources that might go underappreciated sometimes.

In each artwork, it’s the — physical and rhetorical — laying down, assembling, and arrangement of things as they arrive, with unpredictable but smooth progress. A boat that does actually end up getting where you intended despite fluctuating currents along the way. Accomplishment in the realm where objects and component parts to life in general drift into each other, knocking around erratically but keeping the story going.

The reach of each of Jackson’s artworks suggested that kind of encompassing, personal experience, even in the absence of anything obviously representational.

Portraits, Without Figures

But still, I started to imagine each artwork as kind of like a portrait, capturing and molding the kind of thing that accompanies each person as the physical experiences of their life start morphing into mental and emotional sediment.

And Jackson injects lightness into these arrangements of life’s accompaniments, physically lifting these artworks from the ground and from the manner in which you might expect a “painting” to take shape and hang.

Permeability is baked into Jackson’s artistic arrangements, both in terms of that gel itself, which can shift over time, and the unpolished nature of some included components. And under Jackson’s shaping, these acrylics and their many accompaniments become like monuments to finding a way through life. Visual and sculptural components sitting on different wavelengths still have those pulls in diverging directions but unite into something surprisingly uplifting.

I think of sculpture like “Bird in Space” (1923) by Constantin Brancusi, held by The Met, which evokes the (there, particularly voracious) upward, soaring movement of a bird without actually reproducing its features. The large, sweeping, and formidably realized forms of Jackson’s artwork offered similar applications. The space “in between” made into an artistic flight path.

The 2024 biennial’s end date was August 11, but a subset of the art is remaining on view through late September — and that includes the room with Jackson’s work.

Featured image: credits listed above

You may also like

-

Diana Kurz at Lincoln Glenn in New York: A Review of a Shining Art Exhibition

-

Dustin Hodges at 15 Orient in New York City: An Ensnaring Exhibition at an Exciting Gallery

-

Maren Hassinger at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York: Reviewing an Uplifting Art Exhibition

-

Enzo Shalom at Bortolami in New York City: Reviewing an Entrancing Exhibition of Paintings

-

“Ben Werther: Townworld” at Amanita in New York City: Reviewing a Richly Memorable Art Exhibition