In “Romare Bearden & Nancy Grossman: Collage in Dialogue,” a recently concluded exhibition by Michael Rosenfeld Gallery in New York City, the titular artists’ work soared.

The exhibition offered cascades of paper like waterfalls, bolstered by enrapturing flows of extra pigmentation delivered via ink and watercolor. It was paper that frequently had an obvious prior life before incorporation into this artwork, whether the precise origin was not exactly clear… or it was the sardine packaging arranged with care in some of Grossman’s work.

Some of Grossman’s creations lived the furthest from strict narrative, with work by Bearden — who’s no longer living — often outlining a more specified, though still richly layered, scene.

Nancy Grossman & My Desk Drawer

On a logistical level, Grossman’s sculptural, tactile, planar abstractions reminded me of the arc of time as seen in the accumulation of papers — junk mail, receipts, notes to self, shopping lists — in a living space, whether an actual home or just somewhere a lot of living is done, like a workplace where there’s a chance for personalized character to develop. Time grows, and suddenly you encounter a layered reflection of yourself, capturing what was spinning the furthest from your actual person but still connected.

The outer reaches of a day’s jaunt. Life’s driftwood, returned to life.

The spatial rhythms — the song of how Grossman’s reclaimed and re-utilized slips of paper fit together (I’ll return to Bearden’s work shortly) — danced ever outwards.

In some of her work, the adeptly elevated scraps varied greatly, carrying forward that character of prior moments instead of Grossman compressing the aesthetic into something more visually uniform and centralized. She was nodding to linear, linguistic communication but transcending it. Some of the collaged paper — like that packaging — still broadcast direct indications of its previously intended meaning, but that meaning was undone, with the composite, rhetorical strands reassembled someplace else.

And that lived elsewhere — that substrate to our external, top-level artifices in daily life — was here shaped into something surprisingly majestic, honestly. The hints of decay or dissolution were subsumed into a grander, sweeping whole. Grossman’s “Birth-Death Dream” (1993), whose materials include collaged paper, acrylic, ink, and graphite, featured shimmering streaks of orange ripping across the surface: a purposed, invigorating explosion.

Pulling Apart, but Pushing Together

Repeatedly, the march of radiating glimpses of a lived past across Grossman’s surfaces was ensnaring.

You might imagine the individual pieces of paper of her “Light Is Faster Than Sound” (1987–88) hurtling towards each other, with each moment on the Masonite backing given the time to introduce itself before Grossman rockets into whatever arrives next. There, the assemblage of collaged paper is much thicker, burying seemingly the entire backing. Some of it’s a familiar white in color.

Ultimately, Grossman’s positioning of many of her materials allows for the backstory to remain an integral part of the artwork, even if it’s reshaped and she gives it new context.

Edges of Grossman’s assembled assortments of paper appeared sometimes ripped, spinning that particularly forward, physical energy into her overarching tapestries. And it all kept moving, with unpredictable kicks from each bit of attention-grabbing material onward.

Though there are definitely a few visual anchors in that standout artwork from the 1980s, each point on the Masonite shouts out in tandem: a choral infusion of invigorating life and vivacity into moments frozen in a state of falling… that is somehow also a state of these cultivated flashes of familiarity moving into unison. Because those sprawling in form tapestries of movement — movement threaded in each instance to a backstory, a past, a lived moment — turn out somehow welcoming.

As much as you find a refreshing assertion of life in Grossman’s paper journeys, you also find care. While some of the specific reference points connect to the artist’s personal life, she was constructing what seemed like an archetypal, living map, bringing an enveloping sense of presence out of materials that might otherwise be forgotten.

It’s elevating and momentous, moving between the personal and the environmental and systematic while leaving a slippery sense of decay and disrepair as part of the journey that I think is realistic to how much of lived experience tends to actually work, psychologically.

Romare Bearden’s Entrancing Spatial Meditations

Bearden’s spotlighted artworks, meanwhile, incorporated nods to three-dimensional space — though his use of collage did something similar to the human form and its real-world surroundings as what Grossman was doing to the information originally conveyed in some of her ultimately repurposed paper materials. Maintaining the aesthetic linguistics of the human form, Bearden seemed to treat it relationally, placing it amid a cascading landscape of intertwined sights that, perhaps above all else, were truly reflecting, informing, and redirecting each other.

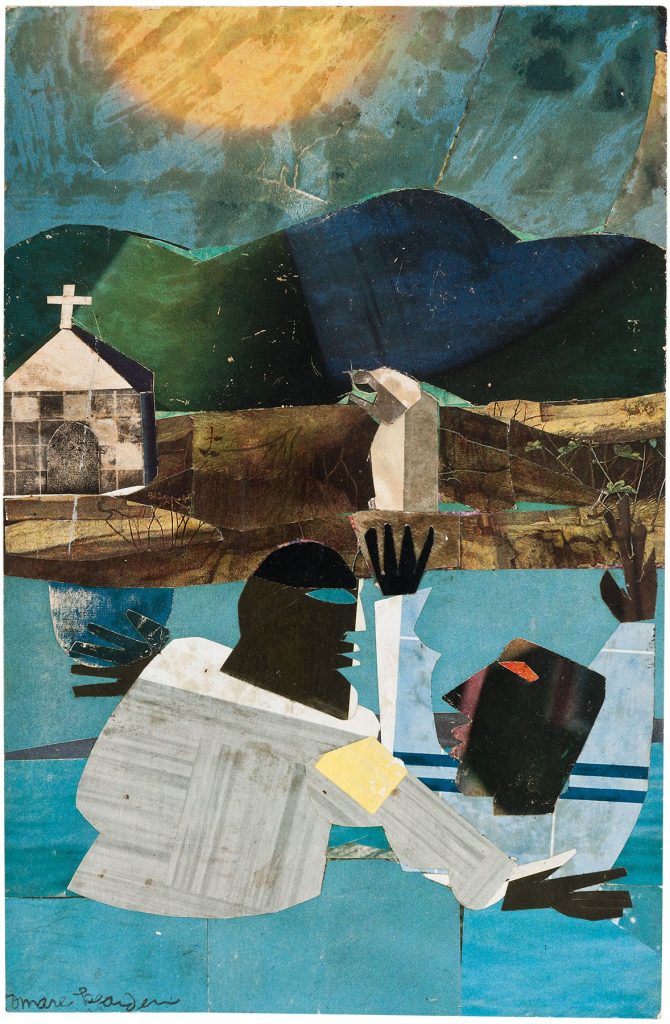

Frankly, it’s been a while since I originally visited this exhibition, but that remains a distinct takeaway that I remember contemplating while standing among the artworks. It’s all encapsulated by one of my personal favorites from the exhibition, Bearden’s “Baptism” (1964).

The scene works outwards, starting at a baptism taking place in a river, beyond which sits an assembled church, rolling hills, and a gleaming sun. And this is all depicted, again, by means of collage that takes particularly shaped pieces of paper and communicates a new series of overarching images in how it all joins together.

The figures in the river are not depicted with anything approaching photorealistic precision, their component parts instead drifting into unison but leaving the visual impression that this particular visual assemblage was almost inevitable, even if it’s something that does not remain fixed in conceptual place. And the figures felt parallel to the church and flickers of surroundings, all communicated with the tangible but fleeting touch allowed by paper, which Bearden (and Grossman) cultivated to stay restrained, skipping from one materialized moment to the next as each piece of collaged detritus builds stirringly upon its surroundings.

Bearden’s “Fish Fry” (1967) felt similar, though the figures participating in the title’s get-together proportionally took up much more of the artwork’s space in this one. But still, individuals became a landscape, and a visual landscape proved itself to be a representation of individuals, with that loop slipping apart but reunifying in tandem.

In allowing the artistic processes they utilized to shine through so clearly in the finished works, Bearden and Grossman used ripping and cutting paper to intertwine a thread of decay, disrepair, and dissolution into their images while making all of that into something comfortable with itself as it visually pulls in different directions but miraculously reassembles.

The exhibition, like I mentioned, is now closed, but I am excited to find other opportunities to see Bearden and Grossman’s work. And I am always engaged by the exhibitions program at Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, so their future offerings are also anticipated.

Featured image: Nancy Grossman (b.1940), “PC 31,” 1963; credits listed above in this article

You may also like

-

Diana Kurz at Lincoln Glenn in New York: A Review of a Shining Art Exhibition

-

Dustin Hodges at 15 Orient in New York City: An Ensnaring Exhibition at an Exciting Gallery

-

Maren Hassinger at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York: Reviewing an Uplifting Art Exhibition

-

Enzo Shalom at Bortolami in New York City: Reviewing an Entrancing Exhibition of Paintings

-

“Ben Werther: Townworld” at Amanita in New York City: Reviewing a Richly Memorable Art Exhibition