I’m always engaged and uplifted when I see the artwork of James Little.

James Little at Petzel

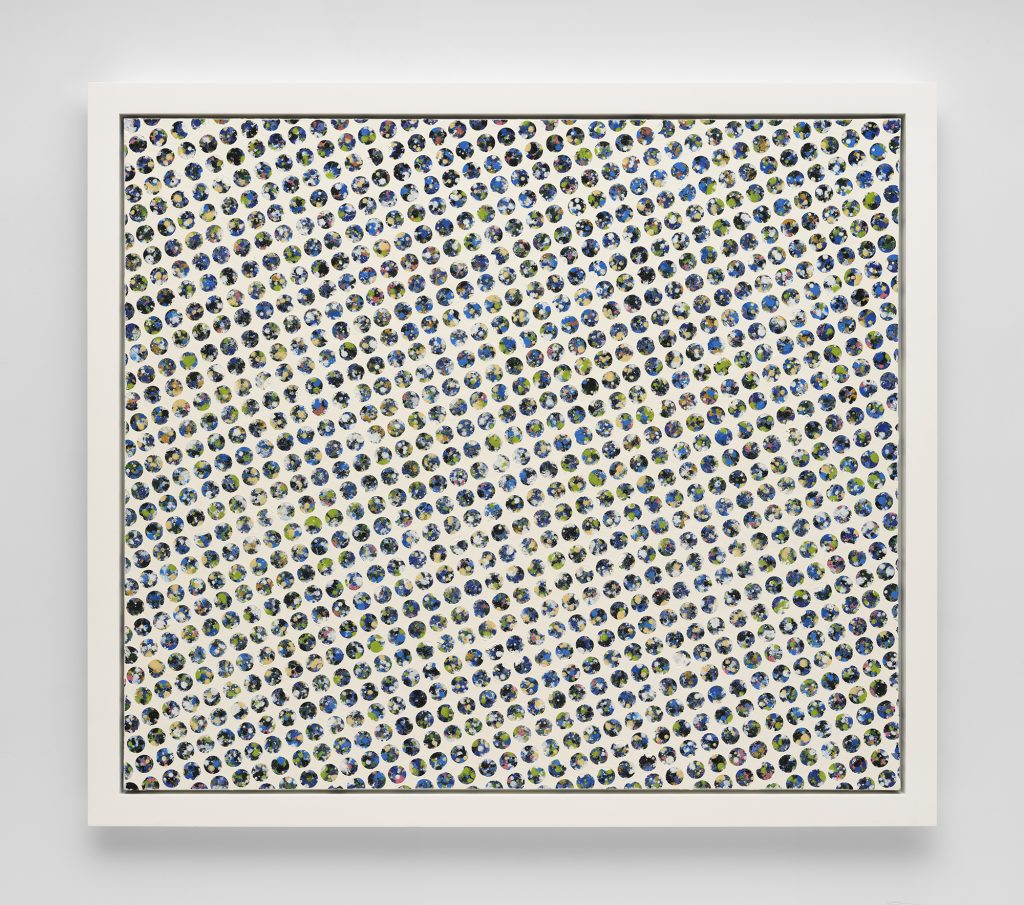

The new, ongoing exhibition “Affirmed/Actions” at the art gallery Petzel in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood showcases a few different — though internally unified — varieties of painting by that artist, including, in one grouping, interplays of speckled smorgasbords of color with overlaid, white patterns.

Those white, aesthetic structures frame the bursting color shining from beneath, reminding me of stained glass windows like in a church, whether an actual, experienced place or something archetypal — or how a real, specific point on the map could morph into its own flowing, progressing character above its original incarnation over time.

One other continuous feature of those paintings is that the openings left by the overlaid white — whether five-pointed stars or circles — are rather small, so the weight of the combined progression from one to the next multiplied to that extent across each artwork’s surface is jarringly buoying.

I feel transmutation and transfiguration in the artworks — including those in the exhibition fashioned differently in terms of aesthetic specifics. They feel like the elevation and cascading of a single moment in time or single person, the latter interpretation driven in part by how Little himself casts the artwork, titling some pieces after real-world individuals from history.

“Portrait of Celia Cruz” (2024), honoring the famous singer born in Cuba, does not depict a recognizable person, but you still get a sense of presence. The expansive cascade of emotionally impactful, expressive color without clear beginning or end feels recognizable. Perhaps it’s an image of the interpersonal and collective, community-wide impacts left by Cruz, moving outwards from their original origin points like ripples or beams of palpable light.

And similar themes and feelings reappeared elsewhere in the exhibition. Both aesthetically and in the titles, Little was nodding to real-world individuals and their environments, but here, you saw those experiential interchanges as part of an overarching, sweeping flow of information and experience: the momentary merging with the more lasting and expansive, while still maintaining its character as something felt.

And specifically, a lot of the color combinations in Little’s works fashioned like the Cruz “portrait” were internally energized, effectively a sweeping capture of how a moment of feeling merges into the next — and on and on, until you’re left, whether in the context of the painting or that of real-world experience, with the felt experience of a thing enveloping you as an embracing wave.

Wholeness

Little’s paintings seem to insist on being read primarily on the level of the piece as a whole.

The paintings blending latticework and bursting fields of intermingled colors, include, if you were to break down each and every point on the surface, simply a massive amount of visual information considering how small many of those individual areas of color are. And other paintings in the exhibition, though also varying in visual texture via using diverging hues and shaping, are primarily black and white (those are two separate groups of work) — making the preeminence of the visual creation as a whole especially central when viewing them.

In each case, the relational flow across the surface of these artworks, when considered in broader groupings, is just remarkably smooth, telling a story of growth and something that cuts across moments with precision and abandon, creating or at least outlining something new and fresh on top of the language of a moment speaking to — or with — the next one. That extra layer artistically captured and expressed here is a linguistics that operates without specifically delineated, grammatical, or even anything anywhere near photorealistic messaging, where instead, the entirety of the painting — in each instance — shines.

And in the visual unity of these paintings — the way that color and form combine, repetitively — that language posits a persistence, and even something eternal, lying behind (though propelling forward) the more temporal and momentary. You often get the sense that, in every direction, these visuals could extend essentially forever, out into space both conceivable and whatever lies beyond that.

Though assertively moving beyond the tangible, Little’s art still builds, grows, and expands, imparting personhood or at least something felt to sweeping fields of color.

Moments of heat or tension are subsumed into a vision that, like an actual stained glass window or an expansive landscape vista, presents something greater. Personal, individualized character merges with landscape, and together, the two categories of visuals and experience blend into a coasting, hulking iceberg of artistically realized ambition. Here, we’re part of something bigger, and that “bigger” thing — taking up our experiences of calamity and familiarity — is drawn from the energy of each interaction while persisting above them.

The ethereal — not literally but… alchemically — feels simultaneously figural here. And these paintings remain persistently ethereal, indeed: cultivated visions where a felt and billowing lightness sweeps across surface after surface.

Little’s exhibition at Petzel continues through December 21, 2024.

Featured image: Installation view, James Little, Affirmed/Actions, 2024, Petzel. Photo: Thomas Barratt. Courtesy the artist and Petzel, New York.

You may also like

-

Diana Kurz at Lincoln Glenn in New York: A Review of a Shining Art Exhibition

-

Dustin Hodges at 15 Orient in New York City: An Ensnaring Exhibition at an Exciting Gallery

-

Maren Hassinger at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York: Reviewing an Uplifting Art Exhibition

-

Enzo Shalom at Bortolami in New York City: Reviewing an Entrancing Exhibition of Paintings

-

“Ben Werther: Townworld” at Amanita in New York City: Reviewing a Richly Memorable Art Exhibition