Artist Neil Jenney’s paintings highlighted in the new exhibition “Idealism Is Unavoidable” at Gagosian in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood are distinctively enthralling.

The paintings feature environments mirroring the natural world that are depicted in startlingly sharp detail. To my eye, the detail looks sometimes too sharp, meaning the approach towards arguable aesthetic perfection housed in the images isn’t quite what we often even see as our real-world senses combine hazy, peripheral views with more central visual perspectives. Actual eyesight can be imperfect. Jenney’s paintings remind me of the striking, sweeping tableaux of director Roy Andersson, and where Jenney takes this subtly surreal touch, where environments become too crisp, is impactful.

Engaging, Startling, and Expansive

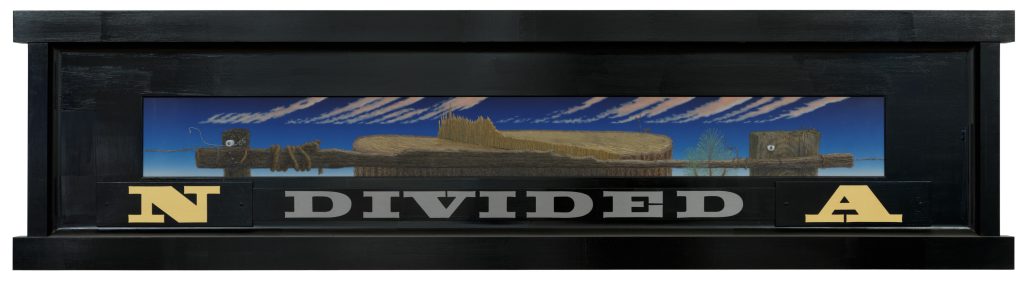

The works (in oil on wood) are large, including rectangles of startling breadth, like one that extends past nine feet. The paintings’ vantage points tend to be cut off; the nine foot-work, 2015’s “North America Depicted,” tops out at just past two feet in height. The painted environments’ sizing smacks of internal realism, and what you’re seeing is ultimately a cut-out across a landscape that clearly extends beyond the edges.

A central element in piece after piece is Jenney’s framing. The painted wood frames smoothly and systematically extend towards viewers much more than the likely expected norm for painting.

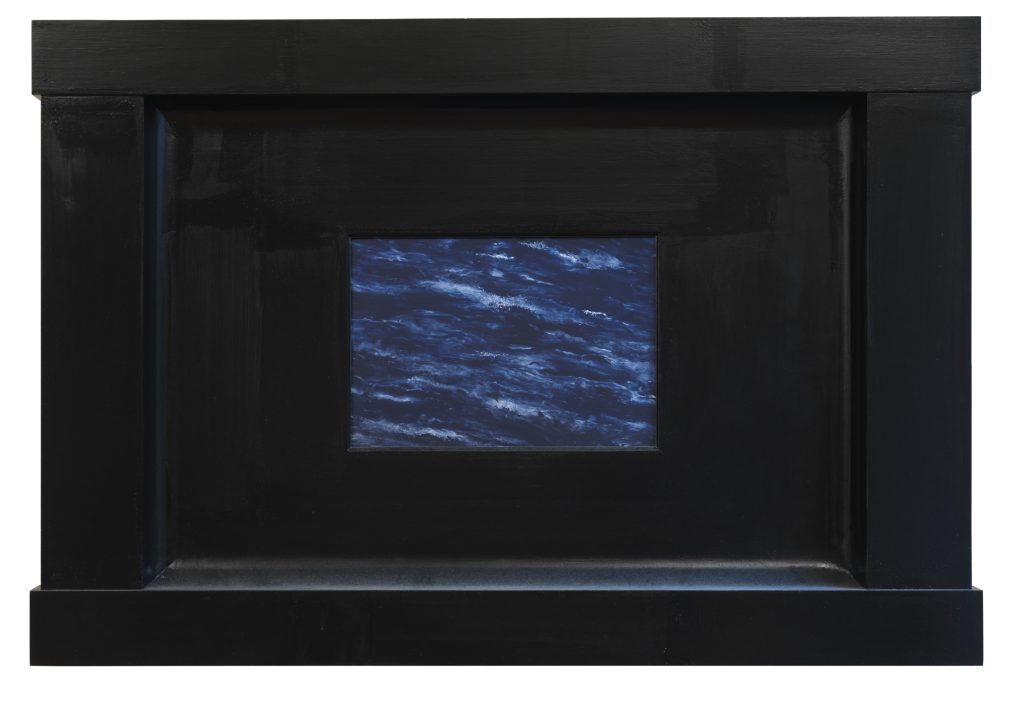

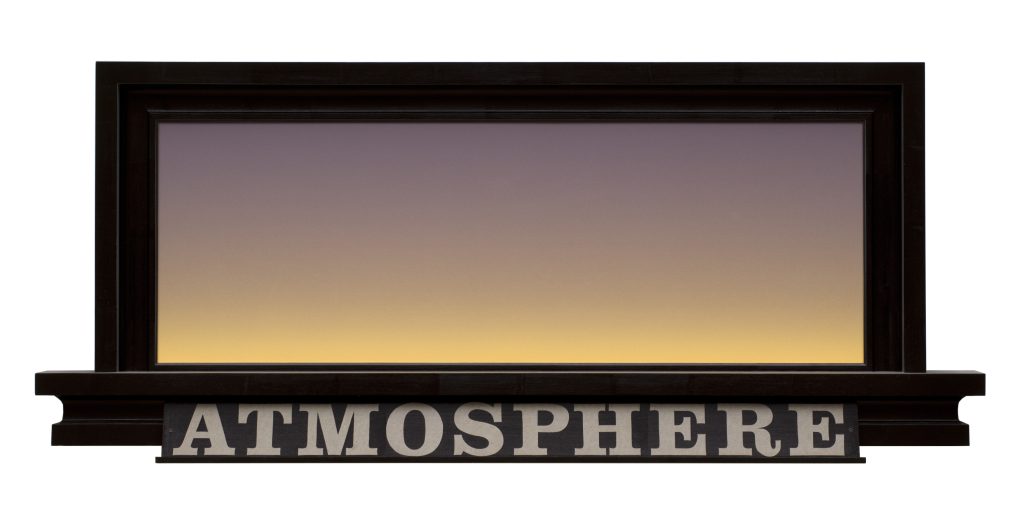

With the artist’s black paint on these utterly striking frames mostly obscuring any seams, the edges are effectively massive blocks of wood, and the centers of these works, where the artist’s painted vistas are housed, sink well behind the frames. The painted images don’t extend to the edge, either, leaving even more space for the resounding visual impacts from the somehow both elegant and hulking framing to ring out.

Every time, the framing quickly becomes its own, unified element, and it comes across like a visual arts representation of someone ringing a gong.

Though the actual structures of the framing are on the minimal side (it’s a smooth visual rhythm awash in black paint, time and again), I was reminded somehow of the intricately constructed, soaring nature of sculpture by the 17th Century sculptor Bernini and artists who worked similarly. The majorly impactful consistency of that side to Jenney’s practice feels simultaneously ominous and heavenly. It’s spiritual and looking upwards, both presenting that push on its own as a sculptural component to the work and drawing that facet out from the environments that Jenney paints.

And linked with the painted scenery, the framing amplified a sense of real, physical dimension to what you were seeing, though the exacting detail already brought tangible environments to mind.

Populating the Scenery

The contents of Jenney’s painted images operated on a wavelength similar to the framing’s spiritual elevation. Despite the detail, Jenney kept the items in the scenes minimal in number. “North America Depicted,” for example, shows portions of a few trees, a stream of clouds, and a slice of the sky. The image part of the 2006-07 work “North American Aquatica” is, at its top level, just an enrapturing view of a body of water with steady waves. Jenney included nothing else, whether nearby flora and fauna or indications of human intervention (though the latter category does show up in other works).

You get the sense that, though seen in the context of the natural world, you’re watching a slow-motion stand-off between unknown spiritual giants. (Think of the Ents from “The Lord of the Rings” for a pop culture cue.) The visual rhythms of those painted lookout points tend consistently towards a sweeping and even searing monumentality.

Even Jenney’s treatment of the sky (and, by association, what we can perceive of the atmosphere when looking upwards) lands similarly, as the mixes of color combine, thanks to the artist’s incisive pictorial precision, into a sense of something unified and maybe even somehow alive.

I’m reminded of how the skies look like their own characters in works by Georgia O’Keeffe, though the particular paths that the two artists take with that area prove distinct.

The surprisingly abridged visual perspectives in the paintings left you compelled to contemplate the overarching visual and emotional impacts of the captured scenes, since you were confronted with their limits in terms of their contents, no matter how precisely painted.

A Fantastical Journey

If I understand correctly, Jenney has worked, at least at times, from a conglomeration of experiences of his own of the natural world rather than painting directly from nature. The scenery, though realistic, is apparently at least partly imagined, and Jenney shares that realm of imagination with his viewers.

A subset of Jenney’s work directly references human intervention in nature, though figures don’t appear. But there’s an ominous undertone, as the specifics include division of the land (like with a visually jarring fence) and acid rain. Every time — placed as they are in sharply defined environments that build throughout their contents at a trudging but subtly celestial pace — the pockmarks of human activity come across like a clarion call or a visually expressed storm siren.

Considering the internal weight that Jenney gives his non-human subjects, these other signs of life — or slow-moving destruction — feel like wounds across what we’re seeing.

Jenney’s “Idealism Is Unavoidable” continues at Gagosian through June 22.

Featured image: Neil Jenney, Idealism Is Unavoidable, 2024, installation view. © Neil Jenney, Photo: Maris Hutchinson, Courtesy Gagosian.

You may also like

-

“Robin Kid: Searching For America” at Templon New York: Art Exhibition Review

-

An Exhibition of Artist Reinhard Mucha at Luhring Augustine in New York City: Review

-

“Mike Shultis: Déjà vu” at Morgan Presents in New York City: Art Exhibition Review

-

Leonardo Drew at Galerie Lelong & Co., New York: Art Exhibition Review

-

“Flags: A Group Show” at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York: Art Exhibition Review