Before my recent visit to “The Rest of Me,” a new exhibition of work by artist Alan Saret at the art gallery Karma, the only piece by Saret that I remembered ever seeing was a wire sculpture on display at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) here in New York City.

The piece was a flowing, billowing cloud of wire that alternated between resounding, even commanding presence in its forceful contours and a difficulty with ascertaining it at all, or at least a feeling that you’re left awash in the light and space housed “inside” of the artwork, considering it was a shaped portion of wire on par with what I’ve seen in contexts like a chicken coop.

Without knowing much about Saret but remembering how I’d been captivated by that particular MoMA gallery’s contents that time around, I expected “The Rest of Me” to feature austere minimalism. The exhibition was not that. I was half-intentionally going in blind, which I sometimes quite appreciate because I’m of a mind to, at least at first, focus on whatever’s actually in front of me before getting context outside of it. Let the piece itself speak, you know?

Trekking through “The Rest of Me”

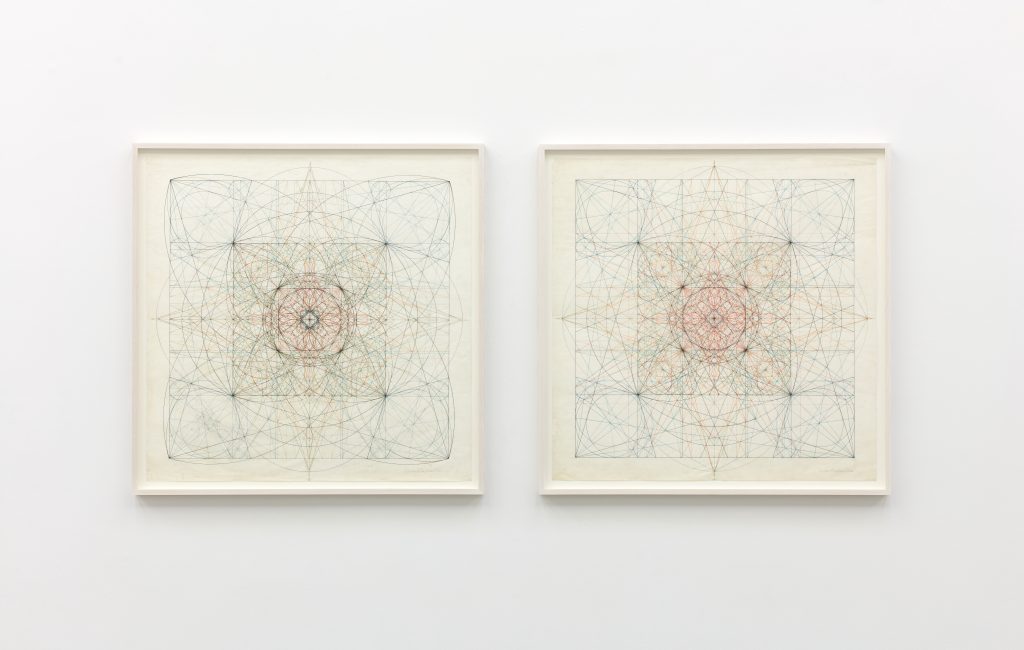

What “The Rest of Me” actually did feature was wonderfully wide-ranging. The exhibition was spread across three viewing locations at Karma in New York City, and I started with a gallery space that was filled to the brim with colorful, swinging geometric compositions that reminded me of what I’ve seen described as the concept of “sacred geometry” — which I discovered was, in fact, Saret’s general intention (getting at something spiritually essential).

Saret’s works at that stop were (largely) on paper and vellum, featuring layers of interlocking lines and forms often filled in with bright, captivating color. The forms are on the level of spatial building blocks — meaning squares, triangles, etc. — rather than strictly representational, although there was some representational art from Saret at another of Karma’s locations.

To be frank, I am not a math and geometry person (currently, at least), and many of these pieces reflected geometric explorations by Saret. But a spiritually uplifting facet to Saret’s compositions — soaring at, one could imagine, a breakneck pace into a blissful intermingling — was still easily glaring, as though standing on the road at night and suddenly finding yourself enveloped in mysterious light.

As much as sometimes it was clear I’d need a guide to grasp all the underpinnings of what I saw, I was quickly hooked. The compositions tended towards a relentless sense of order, no matter the sometimes dizzying array of lines on the page. That order, though, wasn’t rigid. The outlines of Saret’s creations included sweeping curves that blended the heavenward push suggested by historical church architecture (which some of Saret’s forms brought to mind) with, you might say, the welcoming contours of a heavenly cloud indicating the attempt at connection was actually successful.

What if Heaven’s chief inhabitant, however you imagine them, welcomed the tower of Babel instead of setting in motion its destruction?

Lines that Sing

Saret coaxed the lines of these wide-ranging though consistent works into song, as they pull away but push towards each other in uplifting cohesion. Time and again, you find flows of vibration that transform the sharply colored and harshly delineated approach of stained glass windows into something inwardly pulsing, moving beyond that with which we’re the most familiar in terms of physical space but staying firmly rooted to it and its surrounding experiences.

Some of these pieces are wildly complex, but the order remains. You can tell there’s a hand setting these thickets of lines into motion, and not just in a literal sense. It’s a celebration of purposed exploration, finding unity in sharp, focused, incisive, and somehow joyous lines that streak across the page.

It’s surprising — or was to me, at least — how this existential scaffolding really does work, imparting a sense of togetherness.

Saret’s compositions tend to circulate within themselves like a closed loop but defy easy explanation: a combined storm and burst of sunlight in the subconscious, as though the work in front of you and your own innermost mind start having a conversation that you can only kind of piece together. It’s esoteric but — critically — enlivening, as Saret moves through each work with a consistent care.

I particularly liked a series of colored pencil and ink on paper works that all had surprisingly physical heft. “Infinite Aught” (2002, 2024), which is just colored pencil, is a closed, looping infinity symbol turned on its end with a closed, golden loop running through it. Saret filled the inner spaces of these shapes with mostly primary colors but set them against a strikingly dark, luminous background. Everything tends to suggest physical presence while refusing strict compliance.

Looking Elsewhere and Finding Light

Saret’s exhibition also featured a Karma location filled with dharanis. “In Buddhism and Hinduism, a dharani is a sacred, mantra-like phrase to, as he recounts, “recall one’s ideal” during daily activities,” says Karma. Those works on paper were series of text in which Saret put at the center some of the non-literal qualities of these words as he assembled them in space. “First turns being whole alive,” says one, with each word stacked atop the next one.

The calligraphic arrangements were peaceful, moving smoothly through the variations that Saret explored. They were quietly radiant, sticking to the control and focus needed to place these words on a sheet and leave them be. It brought the celestial, experiential light evident in Saret’s other works into what looked like a somewhat more inward context: an establishment of place within the self, allowing your experience of yourself to extend beyond your mind’s walls.

Saret’s figurative drawings at the third Karma location referenced spiritual traditions from around the world, like the Tarot. He seemingly interpreted, for instance, “The Fool” and “The Hanged Man” cards, giving his figures inward illumination.

In a metaphorical sense not a literal one, a lot of Saret’s representational work, alongside pieces elsewhere in the exhibition, looked to be on fire. It was a great time! The exhibition stretched across several decades of Saret’s lengthy artistry.

“The Rest of Me” featuring Alan Saret continues at Karma through June 22. Its next exhibition at its New York locations, kicking off days later, will feature artist Maja Ruznic, who is currently a part of this year’s Whitney Biennial.

Featured image: Installation view of “The Rest of Me” featuring artist Alan Saret at Karma, New York, May 3 – June 22, 2024. Images courtesy of the gallery and artist.

You may also like

-

Diana Kurz at Lincoln Glenn in New York: A Review of a Shining Art Exhibition

-

Dustin Hodges at 15 Orient in New York City: An Ensnaring Exhibition at an Exciting Gallery

-

Maren Hassinger at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York: Reviewing an Uplifting Art Exhibition

-

Enzo Shalom at Bortolami in New York City: Reviewing an Entrancing Exhibition of Paintings

-

“Ben Werther: Townworld” at Amanita in New York City: Reviewing a Richly Memorable Art Exhibition