I felt like a ghost when taking in the paintings from Cold Spring, New York-based artist Amy Bennett that comprise “Shelter,” a new solo exhibition at Miles McEnery Gallery in New York City’s Chelsea neighborhood.

I was already harboring the thought, but it came into sharper focus when I made it to “Dinner Guests” (2024), which like other paintings in the exhibition is quite small, clocking in at 8 x 10 1/8 in.

The contents of the painting are straightforward enough. Someone is greeting two apparent guests at the door, while someone else, presumably their partner, sits inside and around the corner. One could imagine a television playing in that part of the house, but the seated figure doesn’t look like he’s watching it, instead seeming lost in thought.

I interpreted the scene as dealing with grief, though I recognize that’s not strictly demanded by the actual painting. But in how the doorway guests seem to be bringing food along and the passionate tone of embrace as they meet at the door, I felt an internal weight coloring things, slightly clouding my mental vision.

Feeling like a Ghost

The ghostly slant arrived, for me, via how the scene was positioned. You’re looking at things straight on, seemingly as though standing at ground level inside the residence. But nobody in the scene seems to remotely acknowledge your presence, even though that perspective seems to transport the viewer into the flicker of experience captured here, as though you’re a character. You seem present but invisible. Even an included dog is turned towards the door, away from the viewer.

It contrasted with what I’ve noticed a lot in historically traditional modes of painting from Western Europe, I believe, and threads of the same that reached the U.S., where — to me, at least — the viewer’s perspective often seems slightly elevated. It’s probably most obvious in landscape painting. You’re looking at the scene, it seems, from high above, as things slant away from you, creating an obvious sense of perspective that suggests the real world outside of the painting while also reminding you that you’re not a part of it. I’ve sometimes thought to myself that those traditional perspectives place the viewer where God might be, looking down on how things are going.

Even in Bennett’s paintings where the perspective lifts above the ground, you’re still left intermingled in the scene with your suggested presence unresolved. “Cravings” (2023), which features a populated shop seemingly selling bread and baked goods, puts the viewer upwards and at a distance, watching from a perspective that in physical space would probably require unnaturally tall height. You’re towering over the scene as a viewer. It’s alive in some palpable sense, but you’re not there.

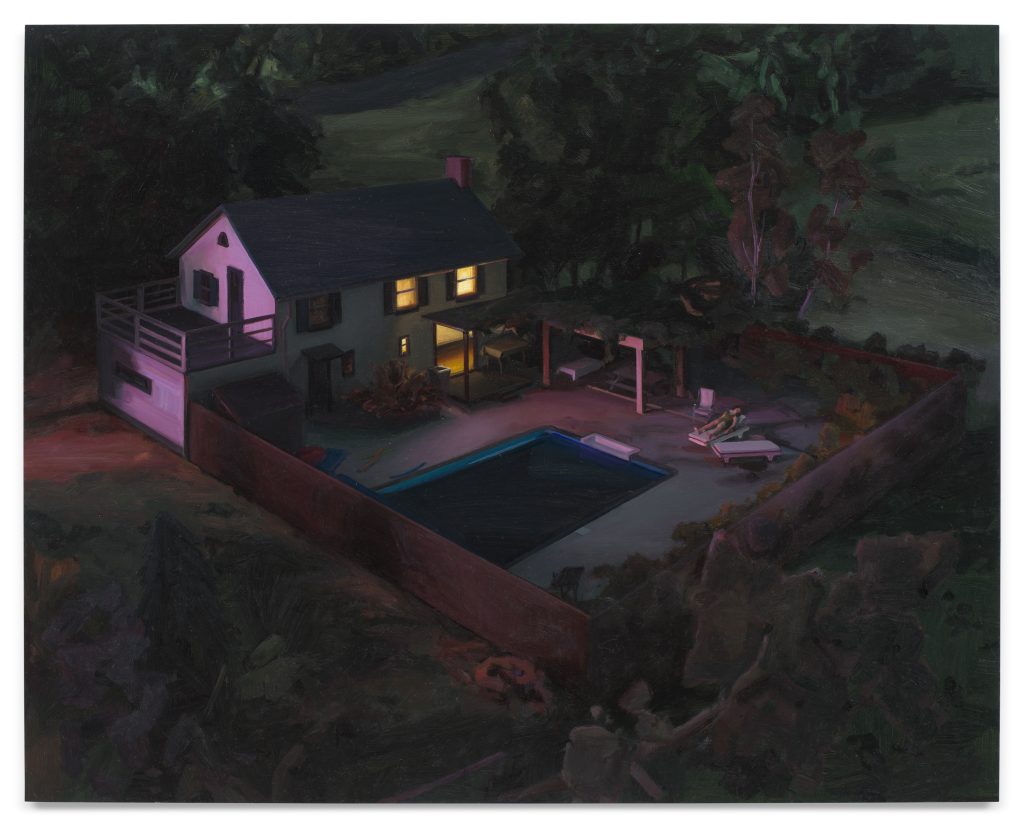

And I was thinking about this thread time and again. “Basking” (2023) places a sunbather in their backyard when it’s actually nighttime, and you’re looking at the whole thing from a perspective suggestive of a nearby hill… or maybe hovering above the trees.

What the News Might Bring

Bennett’s paintings also seemed ominous, as though teetering on the edge of calamity. Perhaps the most obvious of these examples would be “Breaking News” (2023), where a row of television screens, each tuned seemingly to different news channels, show broadcasts that look like they’re focusing on the same thing. (Bennett paints, at times, with artful imprecision.) The screens are on the furthest wall from the viewer, and most of the figures in the scene, which looks like a restaurant, are looking at them — away from you.

Something’s happening. You’re not sure what, but maybe these people aren’t, either. Something’s not right.

Some of Bennett’s scenes were, to be sure, more innocuous.

In the paintings that weren’t, Bennett touched on modern fear, which often strays from something like a bear or physical monster and instead focuses on something that’s more subtly creeping, allowing a veneer of normalcy. I don’t know the extent to which Bennett herself intended to get existential like this, but I think the experience of paranoia at the prospect of what the news will bring next is unfortunately common.

The visual scenes in Bennett’s paintings are constructed carefully and stably, without much obvious structural clash or unraveling. But that leaves that much more room to the surprises that appear. If someone did pass away in the lead-up to the “Dinner Guests” scene, was it you? It’s a fascinating road to travel, placing yourself in the paintings’ worlds like this.

Even without any interpretation quite that theoretically destabilizing, Bennett’s paintings offer a captivating look at an inscrutable fog that flows throughout scenes with which we might be familiar to the point of not giving them a second look outside this context, in our actual lives. There’s something else out there, outside of us, as our environments interact with us right as we are utilizing them. Houses, furniture, campers — these fixtures of the inhabited world seem to operate like characters in Bennett’s paintings, placed on the same visual wavelength as the people who inhabit these mysteries.

Exploring Bennett’s paintings, we can appreciate that drifting, back-and-forth interplay that allows us to develop the experience of a life.

“Shelter,” featuring 17 new paintings by Amy Bennett, remains on view at Miles McEnery Gallery through July 3.

Featured image: Installation view of “Amy Bennett: Shelter,” Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, May 16 – July 3, 2024. Image courtesy of the artist and Miles McEnery Gallery.

You may also like

-

Diana Kurz at Lincoln Glenn in New York: A Review of a Shining Art Exhibition

-

Dustin Hodges at 15 Orient in New York City: An Ensnaring Exhibition at an Exciting Gallery

-

Maren Hassinger at Susan Inglett Gallery in New York: Reviewing an Uplifting Art Exhibition

-

Enzo Shalom at Bortolami in New York City: Reviewing an Entrancing Exhibition of Paintings

-

“Ben Werther: Townworld” at Amanita in New York City: Reviewing a Richly Memorable Art Exhibition